You want to check for strict consistency (linearizability) for your project but you don't want to have to deal with the JVM. Porcupine, used by a number of real-world systems like etcd and TiDB, has you covered!

Importantly, neither Jepsen projects nor Porcupine can prove linearizability. They can only help you build confidence that you aren't obviously violating linearizability.

The Porcupine README is pretty good but doesn't give complete working code, so I'm going to walk through checking linearizability of a distributed register. And then we'll tweak things a bit by checking linearizability for a distributed key-value store.

But rather than implementing a distributed register and implementing a distributed key-value store, to keep this post concise, we're just going to imagine that they exist and we'll come up with some example histories we might see.

Code for this post can be found on GitHub.

Boilerplate

Create a new directory and go mod init lintest. Let's add the

imports we need and a helper function for generating a visualization

of a history, in main.go:

package main

import "os"

import "log"

import "github.com/anishathalye/porcupine"

func visualizeTempFile(model porcupine.Model, info porcupine.LinearizationInfo) {

file, err := os.CreateTemp("", "*.html")

if err != nil {

panic("failed to create temp file")

}

err = porcupine.Visualize(model, info, file)

if err != nil {

panic("visualization failed")

}

log.Printf("wrote visualization to %s", file.Name())

}

A distributed register

A distributed register is like a distributed key-value store but there's only a single key.

We need to tell Porcupine what the inputs and outputs for this system are. And we'll later describe for it how an idealized version of this system should behave as it receives each input; what output the idealized version should produce.

Each time we send a command to the distributed register it will include an operation (to get or to set the register). And if it is a set command it will include a value.

type registerInput struct {

operation string // "get" and "set"

value int

}

The register is an integer register.

Now we will define a model for Porcupine which, again, is the idealized version of this system.

func main() {

registerModel := porcupine.Model{

Init: func() any {

return 0

},

Step: func(stateAny, inputAny, outputAny any) (bool, any) {

input := inputAny.(registerInput)

output := outputAny.(int)

state := stateAny.(int)

if input.operation == "set" {

return true, input.value

} else if input.operation == "get" {

readCorrectValue := output == state

return readCorrectValue, state

}

panic("Unexpected operation")

},

}

The step function accepts anything because it has to be able to model

any sort of system with its different inputs and outputs and current

state. So we have to handle casting from the any type to what we

know are the inputs and outputs and state. And finally we actually do

the state change and return the new state as well as if the given

output matches what we know it should be.

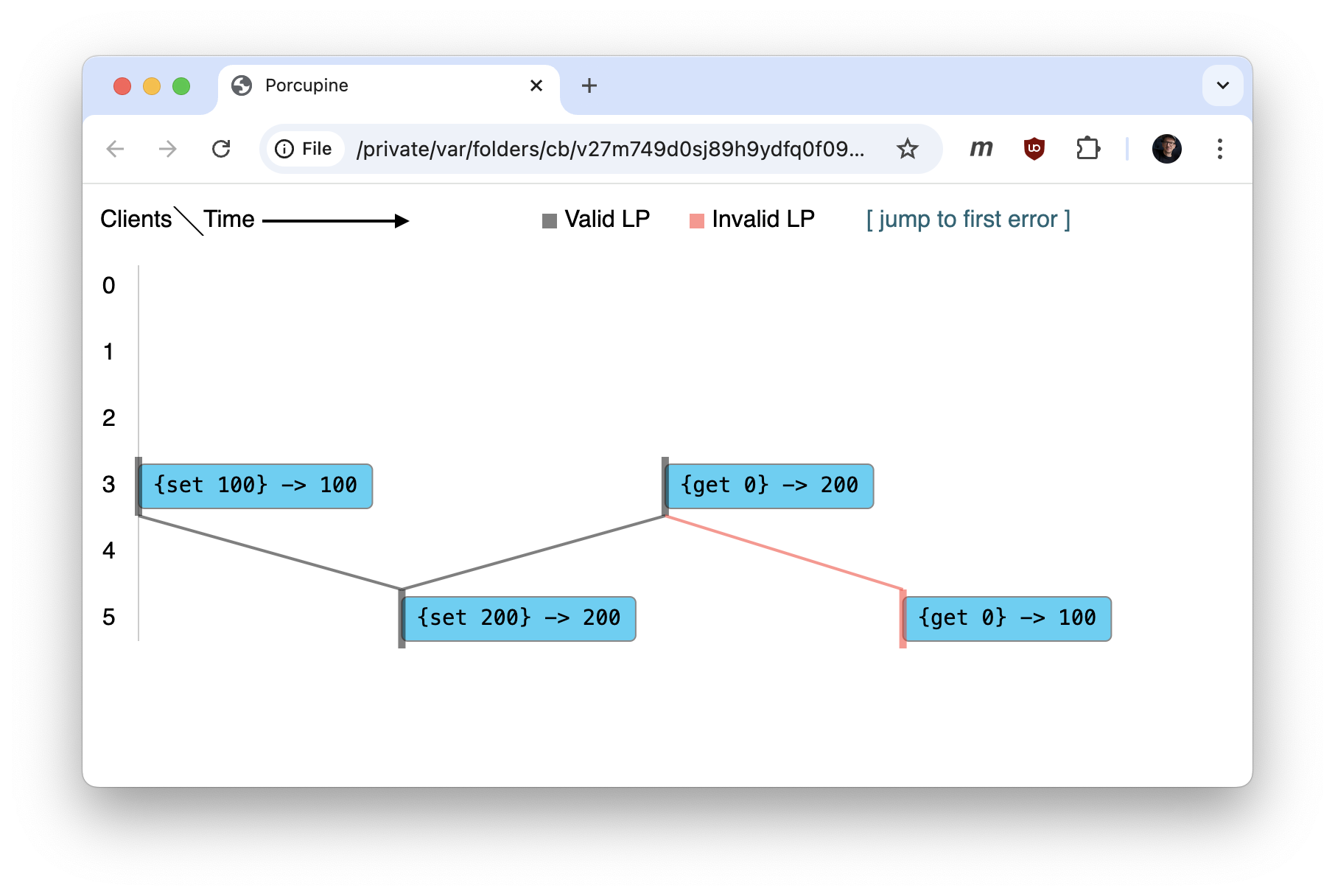

An invalid history

Now we've only defined the idealized version of this system. Let's pretend we have some real-world implementation of this. We might have two clients and they might issue concurrent get and set requests.

Every time we stimulate the system we will generate a new history that we can validate with Porcupine against our model to see if the history is linearizable.

Let's imagine these two clients concurrently set the register to some value. Both sets succeed. Then both clients read the register. And they get different values. Here's what that history would look like modeled for Porcupine.

ops := []porcupine.Operation{

// Client 3 sets the register to 100. The request starts at t0 and ends at t2.

{3, registerInput{"set", 100}, 0, 100 /* end state at t2 is 100 */, 2},

// Client 5 sets the register to 200. The request starts at t3 and ends at t4.

{5, registerInput{"set", 200}, 3, 200/* end state at t3 is 200 */, 4},

// Client 3 reads the register. The request starts at t5 and ends at t6.

{3, registerInput{"get", 0 /* doesn't matter */ }, 5, 200, 6},

// Client 5 reads the register. The request starts at t7 and ends at t8. Reads a stale value!

{5, registerInput{"get", 0 /* doesn't matter */}, 7, 100, 8},

}

res, info := porcupine.CheckOperationsVerbose(registerModel, ops, 0)

visualizeTempFile(registerModel, info)

if res != porcupine.Ok {

panic("expected operations to be linearizable")

}

}

If we build and run this code:

$ go mod tidy

go: finding module for package github.com/anishathalye/porcupine

go: found github.com/anishathalye/porcupine in github.com/anishathalye/porcupine v0.1.6

$ go build

$ ./lintest

2024/10/31 19:54:08 wrote visualization to /var/folders/cb/v27m749d0sj89h9ydfq0f0940000gn/T/463308000.html

panic: expected operations to be linearizable

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.main()

/Users/phil/tmp/lintest/main.go:59 +0x394

Porcupine caught the stale value. Open that HTML file to see the visualization.

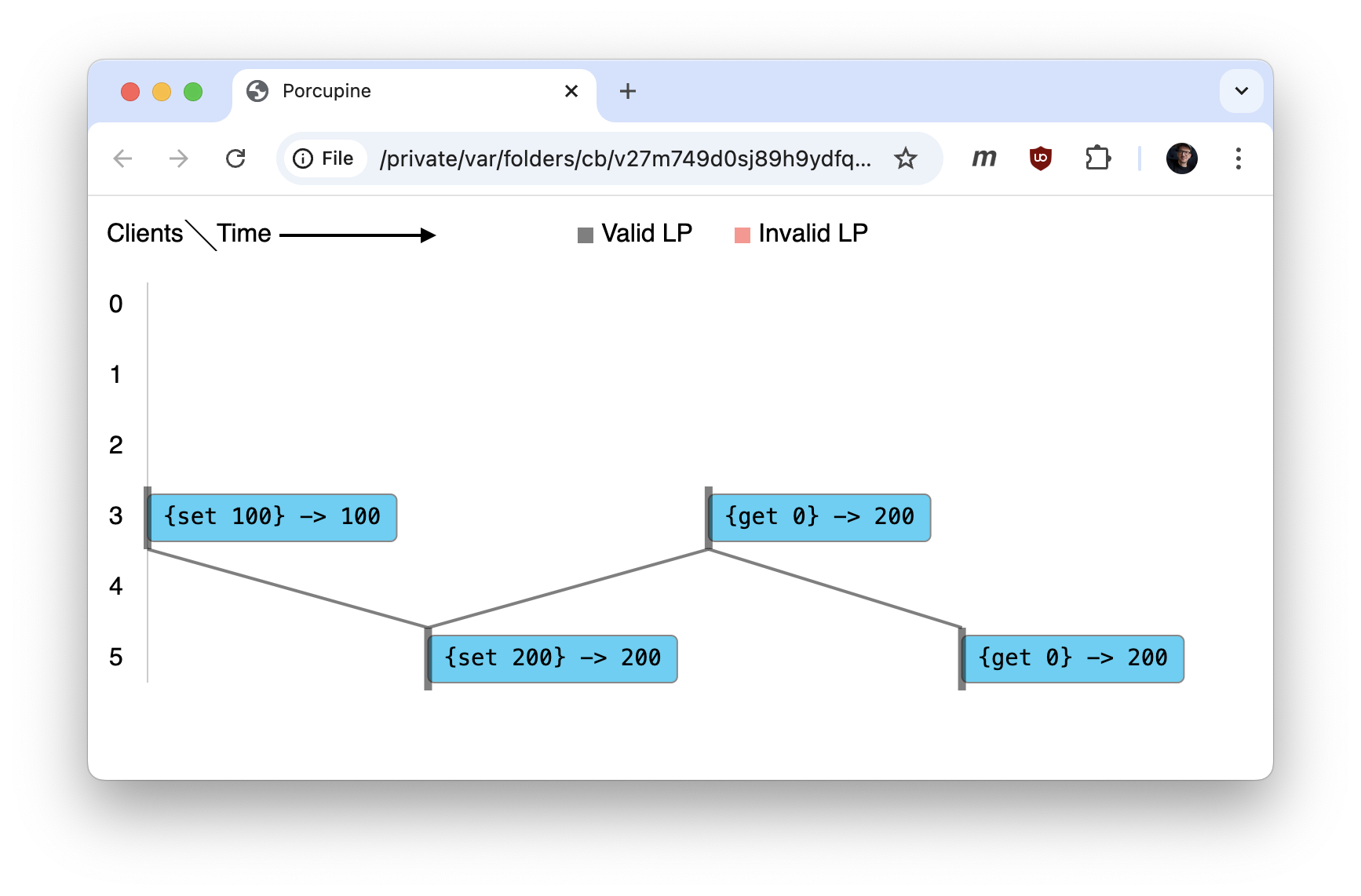

A valid history

Let's say we fix the bug so now there's no stale read. The new history would look like this:

ops := []porcupine.Operation{

// Client 3 sets the register to 100. The request starts at t0 and ends at t2.

{3, registerInput{"set", 100}, 0, 100 /* end state at t2 is 100 */, 2},

// Client 5 sets the register to 200. The request starts at t3 and ends at t4.

{5, registerInput{"set", 200}, 3, 200/* end state at t3 is 200 */, 4},

// Client 3 reads the register. The request starts at t5 and ends at t6.

{3, registerInput{"get", 0 /* doesn't matter */ }, 5, 200, 6},

// Client 5 reads the register. The request starts at t7 and ends at t8.

{5, registerInput{"get", 0 /* doesn't matter */}, 7, 200, 8},

}

Rebuild, rerun lintest (it should exit successfully now), and open

the visualization.

Great! Now let's make things a little more complicated by modeling a distributed key-value store rather than a distributed register.

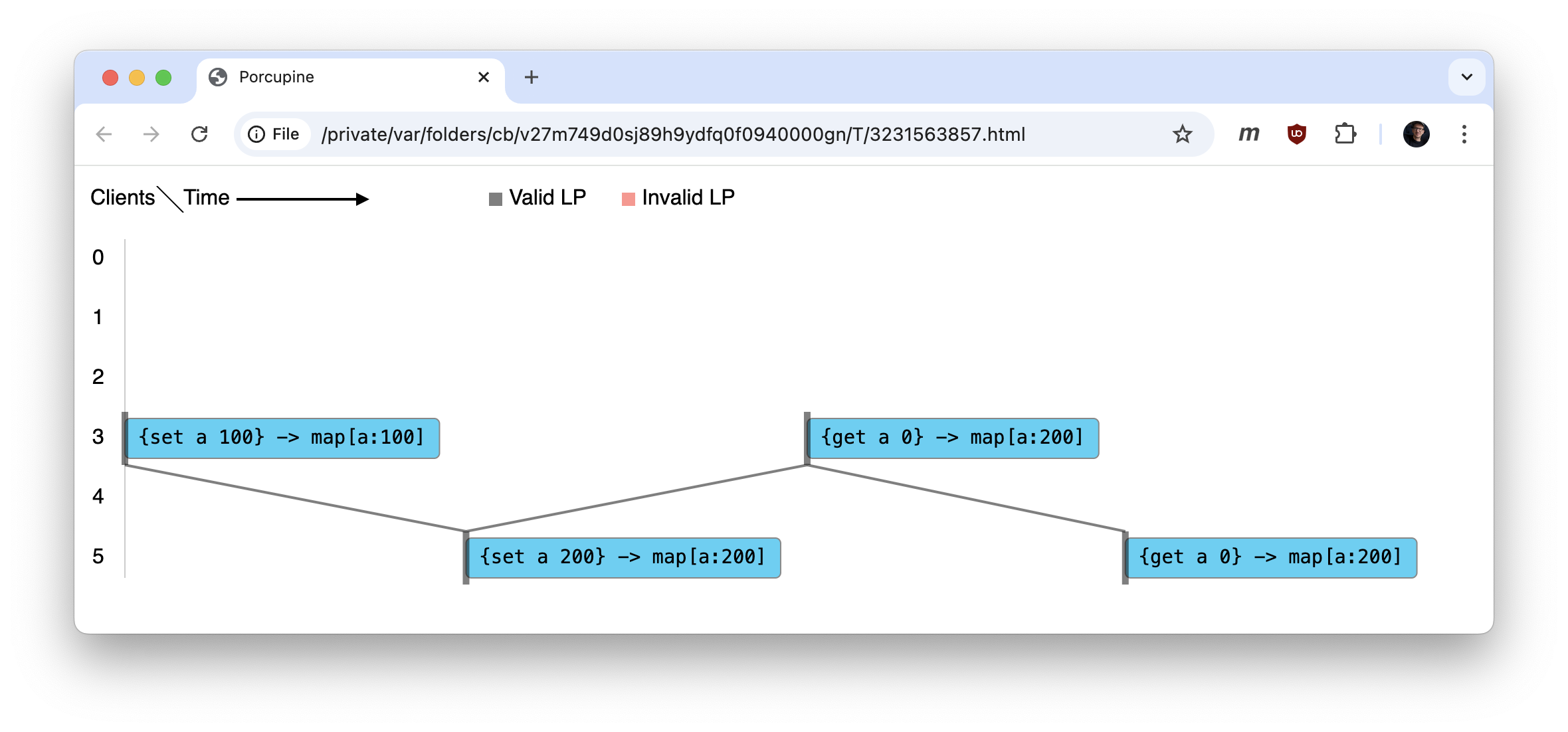

Distributed key-value

The inputs of this system will be slightly more complex. They will

take a key along with the operation and value.

type kvInput struct {

operation string // "get" and "set"

key string

value int

}

And when we model the distributed key-value store with the state and

output at each step being a map[string]int.

kvModel := porcupine.Model{

Init: func() any {

return map[string]int{}

},

Step: func(stateAny, inputAny, outputAny any) (bool, any) {

input := inputAny.(kvInput)

output := outputAny.(map[string]int)

state := stateAny.(map[string]int)

if input.operation == "set" {

newState := map[string]int{}

for k, v := range state {

newState[k] = v

}

newState[input.key] = input.value

return true, newState

} else if input.operation == "get" {

readCorrectValue := output[input.key] == state[input.key]

return readCorrectValue, state

}

panic("Unexpected operation")

},

}

And now the history gets slightly more complex because we are now working with some specific key. But we'll otherwise use the same history as before.

ops := []porcupine.Operation{

// Client 3 set key `a` to 100. The request starts at t0 and ends at t2.

{3, kvInput{"set", "a", 100}, 0, map[string]int{"a": 100}, 2},

// Client 5 set key `a` to 200. The request starts at t3 and ends at t4.

{5, kvInput{"set", "a", 200}, 3, map[string]int{"a": 200}, 4},

// Client 3 read key `a`. The request starts at t5 and ends at t6.

{3, kvInput{"get", "a", 0 /* doesn't matter */ }, 5, map[string]int{"a": 200}, 6},

// Client 5 read key `a`. The request starts at t7 and ends at t8.

{5, kvInput{"get", "a", 0 /* doesn't matter */}, 7, map[string]int{"a": 200}, 8},

}

Build and run. Open the visualization.

And there we go!

What's next

These are just a few simple examples that are not hooked up to a real system. But it still seemed useful to show how you model one or two simple different systems and check a history with Porcupine.

Another aspect of Porcupine I did not cover is partitioning the state space. The docs say:

Implementing the partition functions can greatly improve performance. If you're implementing the partition function, the model Init and Step functions can be per-partition. For example, if your specification is for a key-value store and you partition by key, then the per-partition state representation can just be a single value rather than a map.

Perhaps that, and hooking this up to some "real" system, would be a good next step.

I wrote a short tutorial on using Porcupine to check for linearizability (without needing to deal with the JVM).https://t.co/kqeBz2jX76 pic.twitter.com/teXvlp2zcv

— Phil Eaton (@eatonphil) November 1, 2024